The Constitutional Court

The Structure of the Court

The Composition of the Court

According to Article 135 of the Constitution, the Court is composed

of fifteen judges. The system of nominations is a delicate balance designed

to harmonize various needs: to assure that the judges are as impartial and

independent as possible; to guarantee the necessary level of technical legal

expertise; to bring a range of different knowledge, experiences, and cultures

to the Court, as well as political sensibilities that are not too far

removed from those represented in the political institutions of Italy.

The judges are selected from a restricted category of legal practitioners

with a high level of training and experience. These are judges or retired

judges from the highest levels of the judiciary (supreme magistrature) – that

is, the Supreme Court (Corte di cassazione), the Council of State (Consiglio

di Stato), and the Court of Auditors (Corte dei conti) – law professors, and

lawyers with at least twenty years’ experience in legal practice. There is no

maximum or minimum age limit, but given the requirement of belonging

to the senior magistracy, having a high-level academic qualification or

long professional experience, judges tend to be appointed to the Court in

their fifties, sixties and seventies.

Each judge is appointed for a nine-year term of office (with no age

limit) with a mandate that cannot be renewed or extended; at the expiry

of the term of office, a judge retires or returns to his former profession.

The term of office is longer than that for any other elective mandate

provided in the Constitution. This helps guarantee the independence of

the constitutional judges, particularly from the political bodies that

name a portion of the Court. If a judge leaves office prior to the end of

his mandate, due to death, resignation or removal, his substitute is

named for nine years by the same body that originally appointed him.

As terms have ended early over the years, the fifteen seats on the Court

nowadays generally come up for appointment at different times, with

the result that the composition of the Court changes gradually. In this

way, the Court’s jurisprudence may change over time, but always subject

to fundamental underlying continuities.

One of the fundamental characteristics of the Constitutional Court is

that it is a collegial organ whose decisions are taken collectively, not by a

single judge or a few judges.

Who Selects the Judges?

In apportioning the power to nominate the members of the Court, the

Constitution strikes a delicate and complex balance among the various

needs mentioned above. Five judges – a third of the Court – are elected by

members drawn from the three superior tribunals (three by the Supreme

Court, one by the Council of State, one by the Court of Auditors),

by absolute majority vote of the electoral body; if no such majority is

obtained, the judges are chosen through a run-off election between those

candidates receiving the greatest number of vote. Another five judges are

elected by both Houses of Parliament sitting in joint session, by two-thirds

majority vote in the first three ballots, and three-fifths in all subsequent ballots.

The last five are chosen by the President of the Republic.

The judges selected by the magistracy bring their own particular legal

skills and experiences, and are in no way connected with the choices of

political bodies.

The judges nominated by Parliament (chosen for the most part from

academia and the legal profession, but sometimes from among active

judges) are more likely to reflect the experiences and political sensibilities

found in the representative assemblies and, often, have been Members of

the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies. However, the high number of

votes required to elect them means that it is not simply up to the parliamentary

majority to choose them; normally agreements must be reached

among the different political forces in Parliament. While it is true that

particular judges appointed by Parliament are indeed chosen by the

majority or the opposition, they must then be accepted by both to reach

the requisite number of votes. Reaching such a consensus frequently takes

a great deal of time and a series of ballots. For this reason when new judges

need to be appointed to the Court by Parliament the elections are often

delayed, and the Court continues to function with reduced ranks, that is,

with fewer than fifteen judges, but never with less than eleven. The judges

nominated by Parliament are not representative of, or directed by, the

political forces that put forward their nomination, but are,

like all the other members of the Court, independent of the political parties and of

the Parliament that elected them.

The five judges appointed by the Head of State are normally chosen to

achieve some degree of balance with respect to the choices made by the

Parliament, so that the Constitutional Court mirrors the political, legal

and cultural pluralism of the country as closely as possible.

The variety of legal environments from which the judges are drawn and

the range of political forces that nominate them encourage the presence of

different experiences and specializations (such as criminal, civil, or administrative

law), and different backgrounds and attitudes. What counts most

of all, however, is that the judges are all equal within the Court, and each

makes his own individual contribution to its work.

There are no groups or “parties” in the Court: each judge puts his own

experience and ideas to the service of the Court, regardless of his prior

position or the source of his appointment.

Indeed, the limited number of judges, the collegial method used and

the exclusive nature of the commitment to the work of the Court (during

the term of office judges cannot carry out any other professional activity,

and much less political activity), the length of the mandate and the longstanding

habit of working together mean that the dynamics of the Court

are closely bound up with the personalities of its members. At the same

time, since the decisions of the Court are always collectively made, they

must always be considered the fruit of a collaborative process that integrates

the individual contributions of all the judges.

The Rights, Obligations and Prerogatives of Constitutional Judges

In order to ensure the judges’ independence (as well as the appearance

of their independence), and their dissociation from the interests involved

in Court proceedings, members of the Constitutional Court enjoy special

prerogatives during their term of office, but are at the same time subject

to special obligations.

Constitutional judges cannot be called on to respond officially for the

opinions expressed or votes cast in the exercise of their duties, and cannot

be subjected to criminal proceedings or deprived of their freedom without

the prior authorization of the Court. The Court supplies the judges with

all the support necessary to carry out their work. Finally, the judges enjoy

a salary which is stipulated by law to be commensurate with that of the

President of the Supreme Court, the highest-level career magistrate.

On the other hand, a constitutional judge may not engage in any other

professional activity. This means that those who were magistrates or university

professors (if not already retired) must interrupt their career for the

duration of their mandate (they are considered “fuori ruolo”), and only

return to their former position after leaving office. Those who were active

lawyers cannot practise during their term, or remain members of the bar. All

forms of paid activity, with the exception of receiving copyright royalties,

are prohibited. Constitutional judges are not only debarred from belonging

to political parties, but they may not take part in any political activity.

For the same reason, and as a matter of long-established practice, members

of the Constitutional Court refrain from publicly expressing opinions,

unless in an academic context, or from giving public interviews on

political issues or on questions pending before the Court.

IThe need for the constitutional judges to keep the Court’s inner workings

confidential does not release the institution from the duty to make

the meaning and scope of its activities known to the general public. As for

all decisions taken by judicial bodies, those of the Constitutional Court

too are subject to the obligation to provide a reasoning, so that it will

always be possible to know and consider the reasons underlying them.

However, to ensure that the inevitably highly technical nature of the

Court’s work does not prevent a non-legal audience from gaining adequate

understanding of its decisions, for some time now, the Court has

produced “press releases” on its most important decisions, which it circulates

on social and traditional media.

In addition, pursuant to longstanding tradition, the President of the

Constitutional Court meets members of the press every year to present

what could be called an “institutional stocktaking” of the Court’s activities.

During a special hearing, the President expounds the contents of the most important

decisions of the year in question, illustrating emerging

trends in case law and answering questions by journalists.

Especially in recent years, particular attention has been paid to the

Court’s use of new technologies, with the restructuring of its website and

the use of social media.

Thanks to the Court’s opening to civil society, especially with the

“Viaggio in Italia” (“Voyage through Italy”) initiative, there are many more

opportunities for the Court’s President and judges to publicly express their

views, as well as to explain and clarify the meaning of the Court’s most

important decisions, all the while observing the duty to refrain from

putting their personal opinions before the choices made by the Court.

At the end of his mandate a judge ceases all his functions within the

Court and cannot be re-elected. A retiring judge is conferred the title of

“judge emeritus,” and is entitled to a pension (or to the consolidation of

the services rendered as judge with that of the profession in which s/he

returns) and to end-of-service compensation.

The Presidency of the Constitutional Court

The Court elects its President from among its members for a three-year

renewable term of office (until 1967, the term was of four years and was also

renewable). However, since no judge can remain a member of the Court

after the expiry of his nine-year mandate, it is often the case that the

President – who is normally chosen from amongst the most senior colleagues

in terms of his tenure on the Court – ends his term of office as judge,

and hence as President, before three years have passed. This accounts for the

relatively short length of the terms of many Presidents of the Court, so that

during the Court’s sixty years of existence there have been forty Presidents.

The President is elected by the judges in a secret ballot, by absolute

majority (that is, eight votes in the case of a full Court), and if necessary, a

run-off election between the two judges with the most votes after the second

ballot. To prevent the outcome of the vote of each individual judge from

being known outside the Court, the ballot papers cast in the election are

immediately destroyed following the vote. However, recently, the practice

of publishing a press release, reporting the name of the President thus elected

and the number of votes cast in his or her favour, has been adopted.

The autonomy enjoyed by the Court in the choice of its President reinforces

its collegiality. The President has precisely the same authority as the

other judges in the decisional process, except that his vote breaks any tie

when the judges are evenly divided. He is primus inter pares, whose powers

basically consist of assigning the role of case rapporteur among the various

judges, drawing up the Court calendar of cases to be heard at each sitting,

and convening and directing the work of the Court. He also officially represents

the Constitutional Court (enjoying the fifth highest- ranking State

office after the President of the Republic, the Presidents of the Houses of

Parliament and the President of the Council of Ministers), and supervises

its administrative activity (which is managed on a day-to- day basis by a

Secretary General).

One or two Vice-Presidents, appointed by the President of the Court,

stand in for the President in the event of his absence for any reason. The

President’s Office (Ufficio di Presidenza) has authority to regulate various

organizational and administrative tasks, and committees of judges are set up

to deal with specific administrative functions (such as the preparation of regulations,

and management of the research service, the library, and personnel).

The Administrative Organization of the Court

While the procedures used to carry out the Court’s activities are regulated

by both constitutional laws and statutes, the Constitutional Court –

like the President of the Republic and the two Houses of Parliament and,

in several respects, the President of the Council of Ministers – organizes

its own activity autonomously and possesses the bureaucratic structures

necessary to do so.

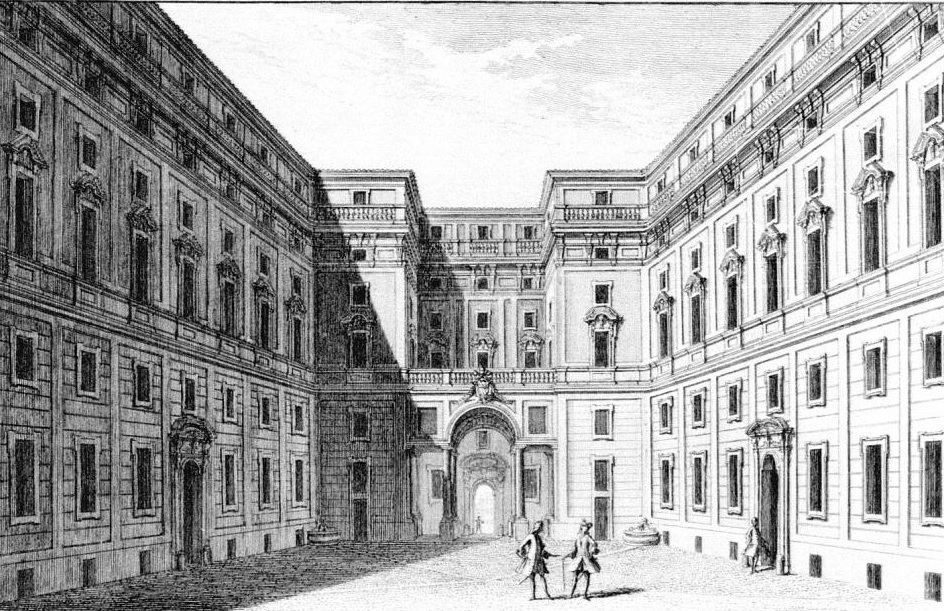

The Court has its own official headquarters and an independent budget

supplemented by funds assigned by the State budget (52.7 million euros in

2016) and published on the Court’s website (www.cortecostituzionale.it).

The Court independently decides on its expenditures, and its internal

organs are free from any external financial auditing or other interference.

The Court has its own administrative support structures for a range of

activities, managed in accordance with its own internal regulations,

including a records office, the ufficio ruolo which assists the President in

the allocation of cases to reporting judges, a research service, a library, and

departments for accounting, purchasing, contracts, and personnel management.

The overall administration of the Court is carried out by the

Secretary General; this is a non-career position appointed by the Court

from among senior magistrates, directors of public administration and

other experts. Moreover, each judge is assisted in his work by up to three

personally chosen assistants. These are research assistants selected from the

magistracy or academia whose job it is to prepare research and documentation

on the issues to discussed by the Court. Judges also have a secretarial

staff that provides administrative support. Altogether, the Court has a

permanent staff of approximately 300 people. The Court enjoys autonomy

in setting the legal and economic terms of employment for its staff,

and is authorised to adjudicate any labor-related claims they may raise.

Such self-government is a privilege that the Italian system has traditionally

also accorded to the constitutional bodies.